HARRIET JACOBS: The slave who visited Steventon

How did a woman born into slavery in North Carolina in 1813 find her way to Steventon, and what did she think of our village?

Harriet’s childhood

Harriet was born in 1813 in Edenton, North Carolina. She was enslaved to the tavern owning Horniblow family. Her mother, Delilah Horniblow (slaves typically took the surname of their owners) had her secretly baptised. Delilah died in 1819 and Harriet went to live with the Horniblow’s daughter. Although she remained a slave, Harriet had the benefit of a kind mistress who taught her to read, write and sew. (Later, in 1830, North Carolina made it illegal to teach slaves to read and write.)

When Harriet was twelve, her owner died and willed Harriet to her three year old niece, Mary Matilda Norcom. Effectively, the child’s father, Dr James Norcom, became Harriet’s owner. A little later, Dr Norcom bought Harriet’s brother, John Jacobs, so that he and his sister could stay together.

A life of misery enslaved to the Norcom family

As Harriet grew older, she experienced a deeply unpleasant side to Dr Norcom’s character. He repeatedly sexually abused her causing his wife to become jealous. Harriet fell in love with a free negro, but Norcom refused to allow them to see each other. Hoping for protection from Norcom, Harriet started a relationship with Samuel Sawyer, a well-known white lawyer. Together they had two children (born in 1829 and 1832). When Harriet became pregnant, Mrs Norcom forbade her to return to the house and Harriet went to live with her grandmother, only a few yards away. Dr Norcom continued to visit her there and made her life a misery.

Seven years in hiding

In 1835, Norcom moved the now 22 year old Harriet to his son’s plantation, six miles away, and threatened to sell her children separately. Harriet decided to escape. A kind white woman hid her, and she later found her way back to her grandmother’s house where she hid in a tiny garret under the roof for seven years. Norcom was furious and reacted by ordering the sale of Harriet’s children and her brother, John. However, the slave dealer was offered a large sum by Sawyer (the children’s father) and so sold all three to him. Sawyer allowed the children to live with their grandmother and Harriet was able to see them through the tiny holes that she bored in her garret wall. She made a living by producing pieces of fine needlework which her friends sold for her.

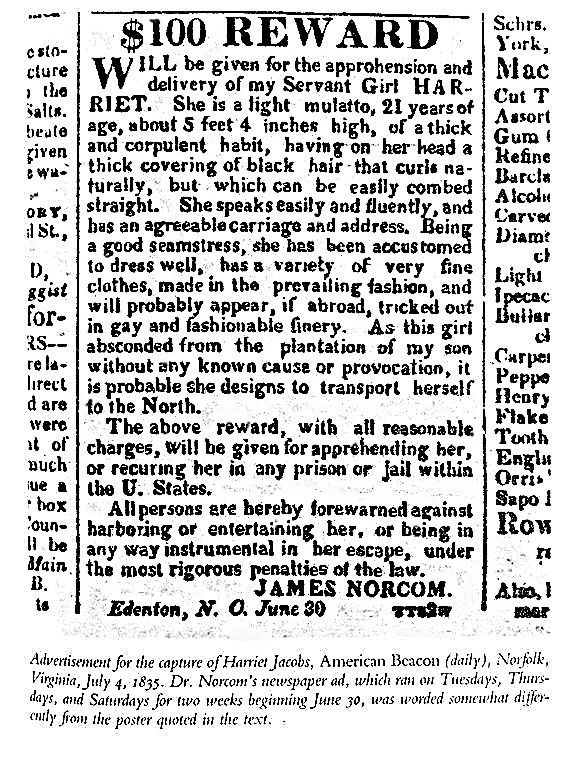

Harriet Jacobs 'Wanted Advert'

Harriet’s escape and a better life with the Willis family

Ever resourceful, in 1842 Harriet escaped by boat to Philadelphia and was helped by anti-slavery activists to get to New York. There she was taken in by the popular writer Nathaniel Parker Willis to be nanny to their baby daughter, Imogen. In the following year, Harriet learned that her whereabouts had been betrayed to Norcom. She fled to Boston where she was looked after by abolitionists.

Harriet travels to Steventon

In March 1845, Willis’s wife died, and he contacted Harriet to say that he was taking his daughter Imogen on a long visit to England so that she could meet her English relatives. He invited Harriet to join them. After a short stay in Liverpool, they arrived in Steventon where Harriet and Imogen stayed with Reverend Vincent in the new vicarage (now St. Michael's House). Reverend Vincent's wife was Willis's sister-in-law. Willis continued on his travels around Europe. Harriet was still a slave but there was a close bond between her and the Willis family, and she didn’t consider using this as an opportunity to escape. Harriet’s book, written when she returned from her travels, provides fascinating insight into what she thought of Steventon.

The 'New' Vicarage

She wrote:

We next went to Steventon in Berkshire. It was a small town, said to be the poorest in the county. I saw men working in the fields for six shillings, and seven shillings, a week, and women for sixpence and seven pence a day, out of which they boarded themselves. Of course, they lived in the most primitive manner; it could not be otherwise, where a woman’s wages for an entire day were not sufficient to buy a pound of meat. They paid very low rents, and their clothes were made of the cheapest fabrics, though much better than could have been procured in the United States for the same money. I had heard much about the oppression of the poor in Europe. The people I saw around me were, many of them, among the poorest poor; but when I visited them in their little thatched cottages, I felt that the condition of even the meanest and most ignorant among them was vastly superior to the condition of the most favoured slaves in America. They laboured hard; but they were not ordered out to toil while the stars were in the sky, and driven and slashed by an overseer, through heat and cold, till the stars shone out again. Their homes were very humble; but they were protected by law. No insolent patrols could come in the dead of night and flog them at their pleasure. The father, when he closed his cottage door, felt safe with his family around him. No master or overseer could come and take from him his wife or his daughter. They must separate to earn their living; but the parents knew where their children were going and could communicate with them by letters. The relations of husband and wife, parent and child, were too sacred for the richest noble in the land to violate with impunity.

Much was being done to enlighten these poor people. Schools were established among them, and benevolent societies were active in efforts to ameliorate their condition. There was no law forbidding them to read and write; and if they helped each other in spelling out the Bible, they were in no danger of thirty-nine lashes, as was the case with myself and poor, pious old Uncle Fred.

I feel that the most ignorant and the most destitute of these peasants was a thousandfold better off than the most pampered American slave. I do not deny that the poor are oppressed in Europe. I am not disposed to paint their condition so rose-colored as the Hon. Miss Murray paints the conditions of the slaves in the United States. A small portion of my experience would enable her to read her own pages with anointed eyes. If she were to lay aside her title, and, instead of visiting among the fashionable, become domesticated, as a poor governess, on some plantation in Louisiana or Alabama, she would see and hear things that would make her tell quite a different story.

My visit to England is a memorable event in my life, from the fact of my having there received strong religious impressions. The contemptuous manner in which the communion had been administered to colored people, in my native place; the church membership of Dr. Flint, and others like him; and the buying and selling of slaves, by professed ministers of the gospel, had given me a prejudice against the episcopal Church. The whole service seemed to me a mockery and a sham. But my home in Steventon was in the family of a clergyman who was a true disciple of Jesus. The beauty of his daily life inspired me with faith in the gentleness of Christian professions. Grace entered my heart, and when I knelt at the communion table, I trusted in true humility of soul.

I remained abroad ten months, which was much longer than I had anticipated. During all that time, I never saw the slightest symptom of prejudice against color. Indeed, I entirely forgot it, till the time came for us to return to America

Freedom at last

When they returned to New York, Harriet lived with a white couple, Amy and Isaac Post. The Posts were staunch enemies of slavery and supporters of women’s rights. In 1850, Harriet returned to the Willis household, His second wife was ill and once again, she became nanny to the Willis children. In 1851, the Willis’s sent her to friends in Massachusetts as they once again believed her to be in danger of recapture. Cornelia Willis bought Harriet’s freedom for 300 dollars so, at the age of 39, Harriet at last became a free woman.

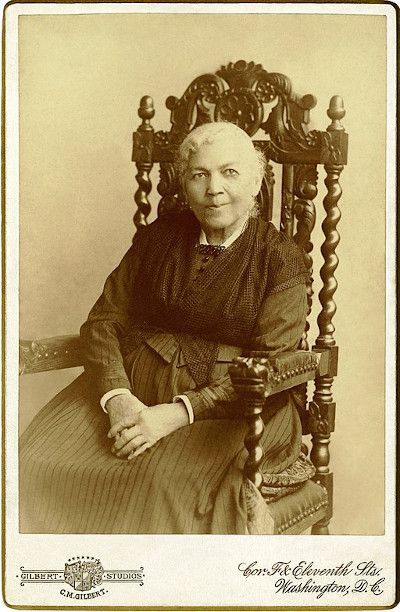

Harriet Jacobs

A successful author

Whilst living happily with the Willis family, Harriet told her story to Amy Post who encouraged her to write her life story, partly as a way of coming to terms with the trauma she had experienced. After a four-year battle finding a publisher, Harriet’s book, ‘Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl’, was published in January 1861. The book was promoted by abolitionists and was a huge success, earning Harriet respect across the Northern states.

Following the book’s publication, Harriet led a busy and fulfilled life. She became politically active and, with her daughter, opened a school for the black community in Alexandria, Virginia. In 1865, after the end of the Civil War, Harriet attempted to start an orphanage and care home for old people in Savannah, Georgia, but her work became too dangerous and had to be abandoned due to the activities of the Ku Klux Klan.

In her old age, Harriet retired to Cambridge, Massachusetts, where she and her daughter kept a boarding house. Harriet died in 1897.

Sharron Jenkinson – on behalf of Steventon History Society

Harriet Jacob's book is available, free of charge, through Project Gutenberg Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl, Written by Herself by Harriet A. Jacobs - Free Ebook (gutenberg.org)

Black History Month

'The extraordinary life of Harriet Jacobs'

and Steventon’s part in her anti-slavery fame

An illustrated talk in St Michael’s Church

Tuesday 15th October 2024 at 7pm